THE DRC - A Policy Memo

What Actions —If Any— should the Congolese Government take to Improve the diffusion of wealth from the mining of Minerals in the DRC

Executive Summary

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) possesses significant reserves of rare earth minerals, including cobalt and copper, which are essential for low-emission technologies. However, the extraction and sale of these minerals have generated negative externalities, including displacement of communities, environmental degradation, and health issues. Artisanal miners, who earn a meager income, contribute significantly to the mining industry, but most of the profits go to foreign companies that refine, process, and transport the minerals.

The root cause of the problem is rent-seeking and regulatory capture by both private and state-owned mining firms. Corruption, human rights violations, and a lack of diversification in industry have led to extreme poverty among the Congolese people . In 2021, the DRC ranked 179 out of 191 on the Human Development Index. The extraction of minerals is often contracted to foreign firms, and revenues are often pocketed by high-ranking officials in the government, leading to a lack of return for the citizens of the DRC.

The Congolese government must take action to improve the diffusion of wealth from the mining of minerals. This includes enforcing environmental regulations, promoting diversification in industry, and renegotiating contracts to ensure that the Congolese people receive a fair share of the profits. The government must also provide alternative sources of income for artisanal miners and invest in education to reduce child labor. Ultimately, it is crucial to address the root causes of corruption and rent-seeking to ensure that the Congolese people benefit from their land's rich biodiversity.

Introduction

Interviews conducted in the Congo’s Cobalt and copper mines in 2 provinces; Haut Katanga, and Lualaba depict the conditions of those that live in nearby mining areas: “What I can tell you is there is no other work for most people who live here… yet anyone can dig cobalt and earn money” (Kara, p.298, 2023). “Parents are pressured to bring their children into the mines to work. If parents earned a good wage, children could be in school instead of working at a mine” (Kara, p.80,2023) There are many multifaceted and interlinked issues within the mining sector that generate a variety of negative externalities that consist of but are not limited to: the displacement of communities due to the expansion of mines, the lack of enforcement of environmental regulations, and a “high rate of birth defects in mining communities, such as holoprosencephaly, agnathia otocephaly, stillbirth, miscarriages, and low birth weight” (Kara, p.76, 2023).

The negative externalities experienced by those residing in the Haut Katanga and Lualaba provinces are vast, and the focus of this analysis will be on mitigating the negative impacts generated from the mining and refining of rare earth metals in the copper belt. The current situation in the Congo’s mining areas stem from the rent seeking and regulatory capture of both private and state-owned mining firms, which in large part are responsible for the negative impacts stemming from the extraction and sale of copper and cobalt.

In Congo, most artisanal miners make an income of approximately approximately 2,000 – 25000 Congolese franks a day (Kara, 2023). This works out to roughly $1.10-$1.40. The World Bank classifies anything under $2.15 as extreme poverty, and in 2018, 70% of the Congolese people lived on less than $1.90 a day, meaning that much of the country currently lives in a state of extreme poverty (Pattison, 2022).

Artisanal miners will spend 12 hours a day digging and sifting through the dirt to fill 40-50kg bags with copper for just under $2.00 (Kara, 2023). These bags are then sold to ‘negociants’, who possess permits to transport the ore to depots that are often owned either partially or fully by foreign companies. These sacks are sold by the negociants for approximately $4.40. From there, they are bought by refiners like Congo Dong Fang (foreign mining firm) and CHEMAF (foreign mining firm), making it almost impossible to separate the industrially mined cobalt from those mined by artisanal miners (Kara, 2023). This process captures most of the profits and allocates it to the firms with the technological capability to refine, process and transport the ore, reducing the diffusion of wealth to the artisanal miners involved in the extraction phase.

The Cause

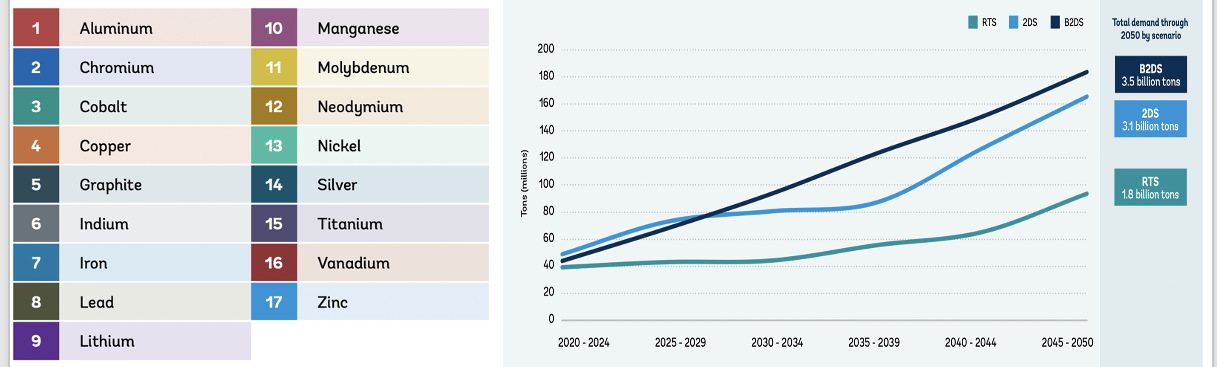

The extractive sector has shifted its focus to the mining of minerals needed for the energy transition to low emission technologies. There are 17 minerals that have been outlined by the World Banks ‘Climate Smart Mining Facility’ that have been pegged as crucial to the development of and transition to low carbon emitting technologies over the next 30 years.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is blessed with an abundance of natural resources, but its people are cursed to bear the weight of externalities that arise from its extraction. From gold and diamonds to oil and gas – the Congo is extremely biodiverse – but the ‘scramble’ to extract these resources has resulted in rent seeking behaviour, corruption, and human rights violations.

Hund, K., Porta, D. L., Fabregas, T. P., Laing, T., & Drexhage, J. (2020). Minerals for Climate Action: The Mineral Intensity of the Clean Energy Transition. The Wold Bank. Retrieved April 24, 2023, from https://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/961711588875536384/Minerals-for-Climate-Action-The-Mineral-Intensity-of-the-Clean-Energy-Transition

The Congo possesses the world’s largest supply of Cobalt (3) and high-grade copper (4), as well as significant stores of nickel (13) Patterson, 2019). In 2019, 72% of the world’s total supply of cobalt originated from the DRC, yet, in 2021 the DRC was ranked 179 out of 191 on the Human Development Index (World Bank), meaning that aside from a select few, most of the domestic population in the DRC has not benefited from their land’s rich biodiversity. This is in part due to the lack of diversification in industry, as currently, a large percentage of the population rely on jobs in the extractive industry. 46% of the DRC’S revenue and 99.3% of its exports come from the extractive sector, forcing many Congolese people into low wage jobs that see little return from the increasing demands for minerals (World Bank).

This lack of return for the citizens of the DRC is quite a complex equation, but it boils down to two problems: (1) that the extraction of cobalt is most often contracted to foreign firms in exchange for a portion of the revenues. The share of profits are majority owned by private Transnational Companies like the aforementioned CHEMAF and Congo Dong Fang. Currently, the Congolese state only has 5% ownership in CHEMAF, and 20% ownership in one of the largest mining sites in the country, Tenke Fungurume (CMOC Limited).

These shares in revenue are also often pocketed by officials high up in the government, as seen in a recent leak dubbed ‘Congo Hold Up’, where it was revealed that a private bank was used to send approximately 135 million dollars of public funds to ‘entities connected professionally or personally to the Kabila family’ (Cloves & Kavanagh, 2021). In 2018, Joseph Kabila’s government spent 230 million on public healthcare — just under 60% of the Public Health Care Budget. In 2021, Germany spent a total of 471 billion euros on a population of 83 million people. The Congo’s population is approximately 92 million. The current structure of trade, in which technology and capital is imported in exchange for rents allows the government to be independent from the population, meaning they have less incentive to invest back into the people. This ‘Resource Curse’ is seen in extractive industries all across the Global South, and leads to a lack of public spending as governments try to retain their power through militant expenditures on security.

In 2019 Tshisekedi was elected to office, and he vowed to combat the poverty in the country and diffuse the income from the Congo’s mineral reserves, but with Kabila’s Font Commun pour le Congo (FCC) still holding key positions of power in state institutions — like Gecamine, the Congo’s state-owned mining consortium — it will prove difficult to work against incumbent interests (International Crisis Group, 2020). Renegotiating agreements between the state owned Gecamine mining firm and foreign mining entities would be a good first step, but the social and environmental costs already experienced from the extractive industry is fundamentally a systems issue.

This leads us to problem number (2), there is a lack of enforcement for the already established policies and laws within the system. The DRC has become so dependent on mining royalties from International firms that they are incentivized not to hold firms accountable for malpractice. They turn a blind eye when communities are displaced as mines expand and firms dump of toxic waste (Kara, 2023)

Market Failures

Negative Externalities

An excerpt from Sidharth Kara’s new book ‘Cobalt Red’, which is filled with interviews from locals across Huat Katanga and Lualaba offers an exclusive and unfiltered look at the realities on the ground. A representative from the University of Lubumbashi researching the health effects of mining on local communities — who has been left unnamed for their safety — states in an interview that his research is more of a nuisance to the Congolese government than it is a tool, as his conclusion illuminated the fact that:

“Artisanal miners have more than forty times the amount of cobalt in their urine as the control groups. They also have five times the level of lead and four times the level of uranium. Even the inhabitants living close to the mining areas who do not work as artisanal miners have very high concentrations of trace metals in their systems, including cobalt, copper, zinc, lead, cadmium, germanium, nickel, vanadium, chromium, and uranium” Kara, p. 79, 2023)

It's clear that the social costs tied to the extraction of cobalt are not being factored into the wages of artisanal miners, and with little to no options for other forms of employment, they’re ‘forced’ to dig for cobalt to support themselves and their families. This feedback loop that many locals are trapped in is clearly beneficial to corrupt officials, hence it’s allowance to continue. In 2024, we face an extremely urgent call to action to both uplift communities and ecosystems that suffer from exploitative industries. It’s no longer an option to do the right thing, but an obligation. If we continue to ignore the root causes of inequality and climate change, the next generation will not have a place to call home. Science, Technology, and innovation are tools within a system, they cannot operate outside of ecology. What we are seeing today is a blatant disregard for the systems limits in the name of greed.

Lack of Public Goods

Informally enforced labor is in large part due to the lack of infrastructure present in mining communities. Entire villages have been displaced due to the expansion of mines in recent years, causing families to lose their homes, and their access to resources such as education and health centers (Kara, 2023). T

Families are forced to work for low wages to fund their children’s schooling even though the state is supposed to fund education for children until the age of (Kara, 2023). Due to the absence of state intervention, schools and teachers are under supported and as such, must charge higher fees to support their livelihoods (Kara, 2023).

The scope of the study does not go into the conflicts in Eastern Congo, where Rwanda and the militant groups M23 are killing innocent civilians due to ethnic conflicts between the Hutus and Tutsis. However, it’s important to acknowledge that any Policy Actions to decentralize and nationalize resources must involve local actors that can speak to the conflict. I am unfortunately unequipped to go into too much detail on this conflict at this moment in time as there focus of the study is strictly on democratizing the extractive industry.

Government Failures

Regulatory Capture

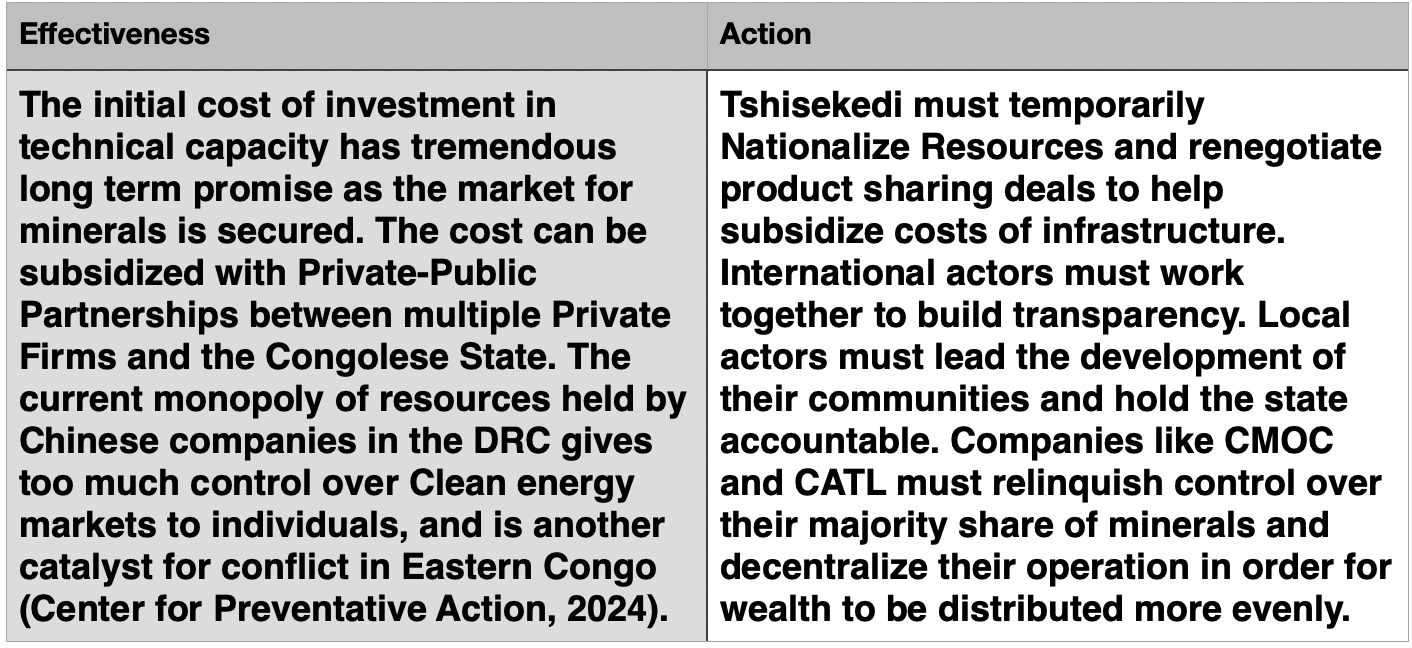

The material capture of wealth by incumbent interests can be seen in the collusion of the Congolese government with both the Chinese State and privately owned firms. In 2007, an initiative called ‘Minerals for Infrastructure ‘agreed to invest approximately 5 billion dollars into new roads and infrastructural elements, in exchange for Chinese state ownership of a total of 10.62 million tons of copper and 620 000 tons of Cobalt (Shed, 2011). The Congolese government would not receive any royalties payed until the loan was paid in full (Kara, 2011). In the private sector, the largest mine in the Congo, Tenke Fungurume is 80% owned by Molybdenum (CMOC) a private firm owned by individual shareholders. The remaining 20% is owned by Gecamine, the DRC’S state owned mining company. Profits from one of the world’s largest Cobalt and Copper mines are either going overseas, or to corrupt officials, and not to the domestic population of the DRC (Gecamine, 2023).

Goals

Protection of Human Rights and Biodiversity

An assessment of the current regulatory framework and its relationships to externalities and living conditions based on new findings must hold governments and international firms more accountable for the social and environmental costs associated with mining.

Diffusion of Wealth

The wages of artisanal miners are secondary to incumbent interests, leading to regulatory capture. By assessing and renegotiating the product sharing agreements between private and state-owned enterprises, a better share of the profits from the mining sector must be invested into systems and infrastructures that increase the quality of living of local communities.

Solution Analysis

Protection of Human Rights and Biodiversity

The burning of fossil fuels and the generation of harmful health effects associated with the mining and refining of cobalt is exacerbated by the lack of environmental protection enforcement.

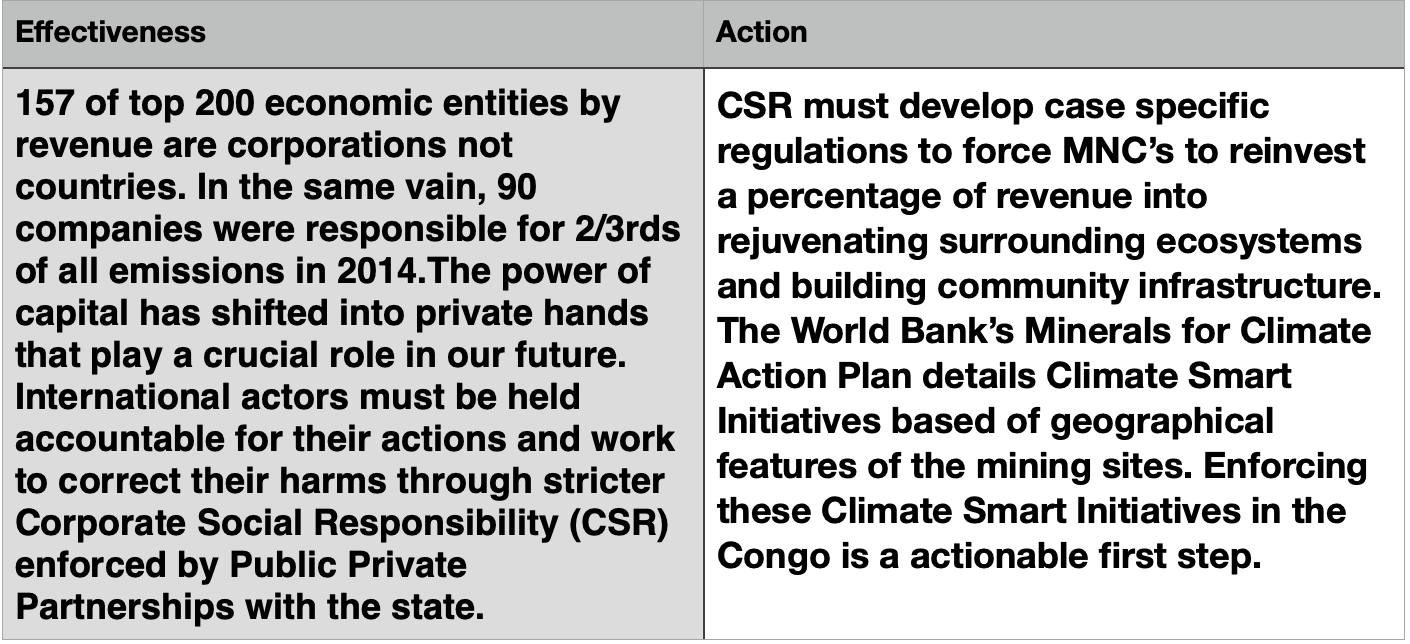

The capital generated from mining presents little reinvestment back into the communities they are affecting. Developing an extensive Policy on Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and an enforcing body is needed to hold those benefiting from mining practices responsible for their generation of negative externalities.

Diffusion of Wealth

Mining firms will experience a temporary loss in revenue due to renegotiated agreements, but a loss of revenue does not mean they will not still be making a profit. As institutions and infrastructures develop, the overall efficiency of local production should improve. Gecamine must receive more than 20% share in Tenke Fungerume. The DRC is a member of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), yet the supply chain is anything but transparent. We are all complicit as a global community in turning a blind eye to the conditions in the DRC, myself included. More local actors must be involved in institutions like the EITI to hold all actors accountable or else they just become performative. The DRC joined the EITI in 2008, but Sidharth Kara’s Cobalt Red (2022) illuminated how shrouded in secrecy the Congo is about it’s extractive industries. I urge you to read his work, as it’s a daring expose of the real conditions on the ground.

Agriculture and tourism industries are under-utilized relative to the natural landscapes in the DRC. These 2 sectors would provide opportunities for jobs, and the development of new and innovative institutions– inevitably benefiting those that have been displaced by the expansion of mining sites, providing them alternatives from of employment and the agency to develop their land as they see fit. Investing in technological capability through applied educational programs will also allow the next generation the autonomy and structure to create new opportunities for innovation within the sector. Think of the beautiful blend if cultural nuance and technological development in the Black Panther Films. It’s about time we decolonize technology and science and diversify the outcomes of research and innovation.

Equity

Relevant groups affected by the mining industry all have their own agendas and goals, but with international institutions calling for cooperation to see the mitigation of climate change by 2030, incentives have never been higher to align goals and find compromises, seeing as what’s at risk are the resources supporting our livelihoods in the transition to renewable energy. What cooperation look’s like is to be determined by local communities. Institutions must start from the Bottom up and give agency and autonomy back to the populations it’s been taken from.

Cobalt refiners and Battery Manufacturers

Incumbent Interests are always trying to make a profit, but an investment in localized infrastructure would benefit their margins in the long term, as it would cut transportation costs, and reduce the emissions associated with the supply chain.

The benefits from the education and sharing of technological capability is first and foremost autonomy. Having more groups capable of complex skilled labor would mean that productivity and efficiency would improve as Systems become Self Organizing and Resilient.

Artisanal Miners

The benefits from investments in education and infrastructure from a renegotiation of product sharing agreements and an Increasingly strict CSR policy would create greater options for mobility and allow kids to go to school without having to worry about supporting their families through dangerous mining practices.

Recommended Policy Instruments

(1) A stricter CSR Policy enforced by SAEMAPE (Service d’Assistance et d’Encadrement de L’Exploitation Minière Artisanale et de Petit Echelle). Must enforce the benefactors of Cobalt extraction to invest in local infrastructure and pay higher royalties through negotiated contracts: specifically the development of STEM programs associated with the development of technological capability.

Instrument Settings:

- A 40% minimum of ownership in the mining consortiums across the 2 provinces

- A minimum investment of 30% of revenue be reinvested into local infrastructure each year by foreign owned mining companies.

- Must diffuse technological capability from higher up the supply chain to the local population.

- Stricter environmental standards in line with the findings of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change ( IPCC)

To improve the diffusion of wealth from the mining of minerals in the DRC, the Congolese government should:.

Diversify the economy: The Congolese government should implement policies that encourage diversification of the economy to reduce the country's reliance on the extractive sector. This would help to create more job opportunities in other sectors and improve the standard of living of the population. Policy bundles may include tourism incentives and investment opportunities as well as a revision of current agricultural industries and production.

Implement and enforce environmental regulations: The Congolese government should take measures to enforce environmental regulations to reduce the negative externalities generated by mining activities. This would include measures to reduce pollution and protect the health of those living in mining communities.

Increase transparency and accountability: All Parties involved in the extraction, refining and manufacturing of materials should take steps to increase transparency and reduce corruption. This would include making mining contracts and Product Sharing Agreements public knowledge, ensuring that mining revenues are used for the benefit of the population.

Build local capacity: Incumbent Interests and Share Holders must be involved in financing local capacity building in the mining sector to increase the value added to minerals extracted and processed in the country. This would help to generate more wealth for the country and reduce the reliance on foreign firms.

Work with international partners: The government should develop Public Private Partnerships with MNC’s and International Think Tanks to develop sustainable mining practices and support the development of alternative technologies that reduce the demand for minerals that are currently causing negative externalities in the DRC.

By taking these actions, the Congolese government could help to improve the diffusion of wealth from the mining of minerals in the DRC, reduce poverty, and improve the standard of living of its population. However, it should be noted that the implementation of these policies would require significant political will and cooperation from stakeholders in the mining sector.

By taking these actions, the Congolese government could help to improve the diffusion of wealth from the mining of minerals in the DRC, reduce poverty, and improve the standard of living of its population. However, it should be noted that the implementation of these policies would require significant political will and cooperation from stakeholders in the mining sector. So, what’s necessary for Rapid Transformation is a shift in Paradigms: from neoclassical economic models of trade liberalization and standardization to resilient heterodox economies built around reciprocity.

References

Diemel, & Hilhorst, D. J. M. (2019). Unintended consequences or ambivalent policy objectives? Conflict minerals and mining reform in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Development Policy Review, 37(4), 453–469. https://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.12372

International Crisis Group. (2022). Mineral Concessions: Avoiding Conflict in DR Congo’s Mining Heartland. International Crisis Group.

Hund, K., Porta, D. L., Fabregas, T. P., Laing, T., & Drexhage, J. (2020). Minerals for Climate Action: The Mineral Intensity of the Clean Energy Transition. The Wold Bank. Retrieved April 24, 2023, from

Patterson, C. (2022). Can the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s mineral resources provide a ... Can the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s mineral resources provide a pathway to peace? Retrieved April 24, 2023, from https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/can-democratic-republic-congos-mineral-resources-provide-pathway-peace

The World Bank, World Development Indicators (2023). GNI per capita, Atlas method [Data file]. Retrieved from http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GNP.PCAP.CD.

Beaule, V. (2023). Artisanal cobalt mining swallowing city in Democratic Republic of the Congo, satellite imagery shows. ABC News. Retrieved April 24, 2023, from https://abcnews.go.com/International/cobalt-mining-transforms-city-democratic-republic-congo-satellite/story?id=96795773

News, B. (2021, November 19). Biggest African bank leak shows Kabila allies looted Congo funds - BNN Bloomberg. BNN. Retrieved April 24, 2023, from https://www.bnnbloomberg.ca/biggest-african-bank-leak-shows-kabila-allies-looted-congo-funds-1.1684433

Sidharth, K. (2023). Cobalt Red: How the Blood of the Congo Powers our Lives.St Martins Press/NY