Ecologizing Infrastructures

Introduction

As a first-generation migrant and a member of the Guyanese diaspora, I often reflect on the distance that has been created to the places I call home. It has been almost 16 years since I have set foot on Guyanese soil. As I navigate early adulthood and reconcile with the idea of ‘Home’, I recognize the privilege I have as a migrant in the West. Yet, I am not of the ‘west’. I am uniquely situated in a plural system of knowledge that is constantly renegotiated. I hope to use this paper to carve out my personal narrative territoriality that informs the ways I understand, engage and make meaning within a world of many worlds (EZLN, 1996). Narrative territoriality – Originally a term used to refer to how stories can create, define and control geopolitical and cultural contexts in the Global South (Bhaba, 2012). In this case, I use it to refer to the reterritorialization of spaces for autonomous self-realization (Illich, 1973; Quijano, 2007). Before introducing the topic, I’d also like to acknowledge my use of complex language. It is a barrier to accessing knowledge, but at this stage in my education, I must use these words to articulate these ideas. I do my best to define terms as I introduce them.

I aim to introduce the beginnings of a lifelong typology (Weber, 1922) – a system for grouping things according to similarities - that will ecologize infrastructure and enrich connections to diverse, interrelated perspectives (Manjapa,2020). Rooted in epistemology, this typology articulates the accumulated and negotiated experiences and knowledge I now use to Decolonize and Delink Development from Modernity’s sociopolitical and material order (Arora et al. 2019; Stirling, 2019; Quijano, 2007). By identifying 3 key infrastructural projects and their close attachments to ‘soft infrastructures’ that reinforce identity politics, we begin to see how coloniality disqualifies and destroys othered worlds through the categorical separation of nature and culture (Harraway, 1991; Latour, 2005; Salamanca, 2016). Each of these infrastructural projects is underpinned by the Guyanese Low Carbon Development Strategy (LCDS), which outlines a progressive and sustainable trajectory, positioning Guyana as a leader in the global charge to decarbonize economies.

My vision for decolonial infrastructure aligns with some of the objectives in the Low Carbon Development Strategy (LCDS), particularly in its recognition of Guyana’s vast natural resources as global assets for Sustainability. However, I disagree with the LCDS market-based approach to conservation through carbon trading and large-scale partnerships. While the LCDS positions Guyana as a leader in the global green economy, it operates within the same neoliberal frameworks that Abadeze seeks to decenter. The question then becomes: How can Guyana leverage its natural resources in a way that not only serves the global demand for decarbonization but also foster a more localized, equitable, and culturally resonant form of development? Abadeze is a Creole word that means ‘we’ or ‘us’. I want it to embody a collective mission to reconnect human and non-human communities through locally embedded community-oriented economies.

Guyana’s Low Carbon Development Strategy (LCDS) – An Overview

Guyana’s forests alone store approximately 19.5 billion tons of CO2, making it one of the world’s largest carbon sinks, and one of only 11 other High Forest Low Deforestation (HFLD) states (LCDS,2022). The title of HFLD is a part of a broader Global initiative by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC) to Reduce Emissions from Forest Deforestation and Degradation (REDD+) (LCDS,2022). The + is meant to emphasize the conservation of and enhancements of ‘forest carbon stocks’ (UNFCC,2021).

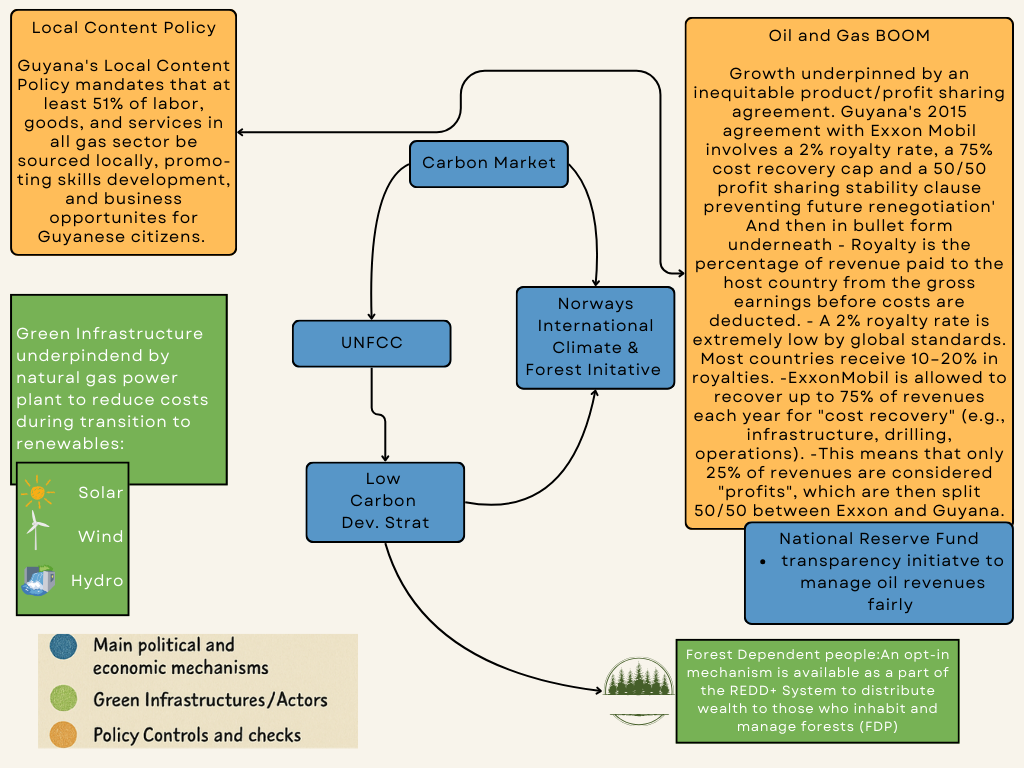

Approximately 85% of the country's territory is occupied by virgin forest (LCDS,2022). In 2009 Guyana became one of the first countries to adopt a LCDS, hoping to leverage and capitalize on the burgeoning carbon trading markets as a source of capital for its Sustainable Development Projects. In leveraging the country's biodiversity as an economic commodity, Guyana has invested in a market-based approach to environmental conservation and Sustainable Development. This in theory gives the Guyanese state the revenue to invest in renewable energy, social infrastructures, green building technologies and low-carbon urban development (LCDS, 2022). Not to mention its recent status as the world's fastest-growing ‘green’ economy – due to its oil revenues produced from the Stabroek field. Guyana's projected status as the 16th largest oil exporter by 2027 complicates its natural resource management strategy as an HFLD state. While a model can never fully illustrate the complex networks of global actors and market mechanisms (seen in Figure 1), figure one attempts to give a broader overview of actors and their Political, Environmental or Economic motivations.

figure 1

Since 2009, The LCDS has evolved through partnerships with entities like Norway, The UNFCC and Exxon, reinforcing the commodification of nature within a neoclassical anthropocentric framework that turns nature into a tradeable commodity (Haraway, 1991; Latour, 2005). While I agree with the need for the development of green technologies, I think it’s time to recognize the need to develop them through a more equitable and innovative framework. Mcafee’s ‘Selling Nature’ argues that the commodification of nature abstracts our relational accountability to the spaces we occupy (Mcafee, 1999). While the LCDS presents a framework for sustainable development through market-based mechanisms, it operates within a broader system of 'hard' and 'soft' infrastructures that reinforce modernity’s socio-political order (Salamanca 2016; Arora et al. 2019; Stirling, 2019).

‘soft’ infrastructures — such as education systems, legal frameworks, planning institutions, technical standards, and even development imaginaries — work more subtly to uphold the epistemologies and rationalities of modernity (Arora et al., 2019)‘hard’ infrastructures refer to the physical, material systems such as roads, dams, electrical grids, pipelines, and data centers — often seen as the backbone of development and modern statecraft. These structures are deeply embedded in colonial legacies, acting as tools of territorialization, enclosure, and extraction (Salamanca, 2016).

These infrastructures, shaped by colonial legacies, geopolitical power relations, and environmental pressures, reveal deeper tensions in how we occupy and manage space. To better understand these dynamics, we must examine how these hard and soft infrastructures influence the management of both natural and built environments.

Hard and Soft Infrastructures of Modernities Socio-Political and Material Order

Due to the scope of the essay, I utilize case studies to augment my arguments and build relationality. Prioritizing economic development often overlooks the need for adaptable infrastructure. With 90% of Guyana's key infrastructure on vulnerable coastal plains, the country faces risks from sea level rise, extreme weather, and ecosystem degradation (IPCC, 2024). Sarah Vaughn’s work on rethinking innovations having to do with mitigating sea level rise is useful as it illuminates how the built environment (in this case the sea walls) are an impermanent solution to the complex interactions of the shoreline (Vaughn, 2022). The sea walls were initially commissioned by the British Colonial Administration and maintained ever since. Infrastructures can be broadly categorized as major or minor. Major infrastructures are typically large-scale, state- or corporate-driven projects—such as highways, oil pipelines, or sea walls—that operate within the frameworks of global capitalism and modernity (Salamanca, 2016). These infrastructures often perpetuate extractive practices, centralize control, and reinforce existing geopolitical power relations.

In contrast, minor infrastructures—such as community-managed renewable energy systems or local water conservation initiatives—are smaller in scale, decentralized, and prioritize local knowledge, autonomy, and ecological relationships (Salamanca, 2016). The sea walls are under constant repair and require capital-intensive investments to maintain. Engineers have begun to acknowledge the complex interactions between natural phenomena and seek to work with the dynamics of the shoreline to develop infrastructures that entangle nature ecology with culture and technology (Kreig et al, 2020; Parika, 2015). One such solution, ‘Soft Groynes’ uses biodegradable materials to trap and retain sediment to restore the surrounding ecosystems (Vaughn, 2022). Unfortunately, these alternatives, according to Vaughn’s study are underfunded and rely on International Donors. With the influx of revenue coming into the country, these solutions must be pushed higher up on the government’s agenda.

A larger ethic of relational accountability – which acknowledges relationships do not merely shape reality but are reality must be integrated into Guyana’s governance and greater systems of knowledge (Wilson, 2008). If we are to work towards building a livable future that fosters a political, economic, social and ecological responsibility, we must design systems and conduct experiments that delink Modernity from the binary oppositions of culture and nature, subject and object, subject being the superior and object the inferior to be acted upon Arora et al. 2019; Stirling, 2019; Illich, 1973).

Identity politics

These rigid binaries not only shape how we design and manage infrastructure but also structure identity and power in society. Like physical infrastructures, identity politics can either reinforce or challenge existing hierarchies (Velasco,2020). In Guyana, political infrastructures—similar to physical ones—have long been shaped by colonial legacies, with identity serving as both a tool for division and a means of leverage in the post-colonial landscape (Constantine, 2024).

Collin Constantine’s analysis of national household income, electoral outcome data and Guyanese demographic data from 2006 to 2021 illuminated the ways in which ethnic identity was used as leverage to consolidate support for political parties. Identity politics refers to the generalizable categories marginalized populations are traditionally grouped into (Velasco,2020). In the case of Guyana, political alliances reinforce manufactured racial hierarchies embedded within the narratives of the colonial era. The Peoples Progressive Party (representing the Indo-Guyanese) and the Peoples National Congress (representing the Afro-Guyanese) have deep rifts as they individually developed a distinct cultural and social identity within the confines of colonial institutions. It’s not uncommon for these ethnic divides to influence socioeconomic inequalities, as is the case in Guyana, where Indo and Afro-Guyanese communities are attempting to exclude one another from fully participating in economic activities (Constantine, 2024).

My family, being affiliated more towards Afro-Guyanese (PNC) political frameworks, have expressed their concerns that the PPP is corrupt and ‘only look out for themselves’. Despite this sentiment, it must be said that the PPP has put in place controls to ensure transparency in just management of resources for the benefit of all Guyanese citizens. Most saliently, The National Resource Fund (NRF) and the country's work on Local Content Policy has put in place controls that attempt to manage Guyana’s unique situation appropriately and democratically. The PPP has attempted to diversify its portfolio and invest in the Guyanese people (LCDS, 2022). Despite this, there are still questions surrounding the legitimacy of the PPP’s intentions. Demerara Waves Online and News Source Guyana provide examples of Guyanese citizens disappointed in the lack of wealth diffusion – citing the favouritism of well-connected contractors and companies affiliated with Indo-Guyanese communities. Geopolitical power relations constructed during colonial times have created conditions in which soft infrastructures of Policy and Regulatory frameworks privilege some but not others (Salamanca, 2016).

Moving Beyond the Market – Towards the Pluriverse

The pluriverse has no universal design, yet locally embedded knowledge systems recognize the interrelatedness within our ecological home. This awareness must guide how we manage our shared environment to sustain its complex relationships. (figure 2). I fully recognize that it’s not simply a case of just leaving the oil in the ground. Guyana’s President, Mohamed Ifraan Ali has been outspoken in his demand for reparations his people deserve, as a part of the colonial legacy of racialized capitalism (Robinson, 1983). President Ali is not shy in sharing the fact that the prosperity and development of the West is directly associated with the exploitation, displacement and extraction of differently situated diverse peoples from the ‘Global South’ (Navara Media, 2023). I believe that Guyana has every right to utilize its natural resource wealth to uplift its people and provide them with the freedom to build a world where they can feel fully self-realized within (Illich, 1973). What we will come to see as we trace the soft and hard infrastructures back to their roots, we will come to see how extraction, exploitation and objectification have affected the way we manage our Home.

figure 2 (Adapted from Satish Kumar’s key not speech at Ted x

Discussion and Conclusion

While grouping elements of similarity, this typology reflects the inherent complexities of infrastructure, identity, and ecological relationships. Decarbonization and sustainability are not merely technical challenges—they require deep engagement with socio-political, cultural, and historical contexts.

It is through the lens of Abadeze that I envision a more relational and community-oriented model for infrastructure—one that is embedded within local context, responsive to the needs of both human and non-human actors, and capable of fostering a more equitable and culturally resonant form of development. By embracing locally embedded experiments—projects that emphasize relational accountability and a pluriversal understanding of knowledge and power—there is potential to transform market-based infrastructures into systems that support community-oriented economies (Gibson-Graham 2006). This includes reconceptualizing ‘soft infrastructures’ like policy frameworks and regulatory systems, ensuring that they do not reproduce colonial hierarchies or modernity’s binaries, but instead enable more adaptable, flexible, and just infrastructures.

Moving Forward: The typology would benefit from a project-based study within Guyana, working closely with local communities, government, and other stakeholders to reimagine and reorganize market-based economic infrastructures into locally embedded experiments. These initiatives should prioritize decolonizing both the epistemic frameworks and material practices that have long governed infrastructure, recognizing that truly sustainable development must go beyond global carbon markets and speak directly to the lived realities of people and ecosystems on the ground.

This approach would seek to build community-led, minor infrastructures that not only decarbonize but also delink from the broader neoliberal frameworks that often constrain genuine, culturally grounded sustainability. As Guyana continues its journey toward becoming a global leader in the ‘green’ economy, it must balance its participation in the global market with the preservation of its rich cultural, social, and ecological heritage. Through this careful balance, we can envision a future where people and the planet thrive within a more equitable and sustainable pluriverse.

The vision for Abadeze—a term symbolizing collective belonging and mutual care—reminds us that sustainability's future is not only in large-scale technological solutions or market innovations, but also in the recovery and revitalization of locally embedded knowledge and systems. These two dimensions are not separate; rather, they are in constant dialogue. Technical solutions can inform locally embedded practices, and vice versa. By fostering this reciprocal relationship, we can create infrastructures that are not only adaptive and resilient but also deeply attuned to the complexities and diversities of our world, ultimately contributing to a more just and sustainable future."

References

Amin, A. (2014) ‘Lively infrastructure’, Theory, Culture & Society, 31 (7–8), pp. 137–161.

Bhabha, H. K. (2012). The location of culture (2nd ed.). Taylor and Francis.

Constantine, C. (2024). Income inequality in Guyana: Class or ethnicity? New evidence from survey data. World Development, 173, 106429-. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2023.106429

Doyon, A., Boron, J., & Williams, S. (2021). Unsettling transitions: Representing Indigenous peoples and knowledge in transitions research. Energy Research & Social Science, 81, 102255-. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2021.102255

e, L. C. M., & Blaser, M. (Eds.). (2018). A world of many worlds. Duke University Press.

Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional / Zapatista Army of National Liberation. (EZLN) (1996). Fourth Declaration of the Lacandona Jungle.

Escobar, A. (2018) Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. Durham: Duke University Press.

Gibson-Graham, JK. (2006). A Postcapitalist Politics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Glendinning, S. (2011). Derrida: a very short introduction. Oxford ; New York, Oxford University Press.

Government of Guyana. (2022). Low Carbon Development Strategy. https://lcds.gov.gy/

Haraway, D. (1991) Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The reinvention of nature. London: Routledge.

Helman, C. (2024, May 7). Guyana’s outspoken president Irfaan Ali has billions of reasons to embrace an Exxon-led oil boom. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/christopherhelman/2024/04/30/guyanas-outspoken-president-irfaan-ali-has-billions-of-reasons-to-embrace-an-exxon-led-oil-boom/

Helman, C. (2024b, June 3). Guyana Touts Itself As Capitalist Paradise - For More Than Just Big Oil. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/christopherhelman/2024/05/09/guyana-touts-itself-as-capitalist-paradise---for-more-than-just-big-oil/?sh=6c29c2e07994

Illich, I. (1973) Tools for Conviviality. Glasgow: Fontana/Collins.

Krieg L, Barua M,& Fisher (2020, November). Ecologizing infrastructure: Infrastructural ecologies. Ecologizing Infrastructure: Infrastructural Ecologies https://www.societyandspace.org/forums/ecologizing-infrastructure-infrastructural-ecologies

Kumar, S. (2013, February 13). Education with hands, hearts and heads [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VAz0bOtfVfE

Latour, B. (2005) Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-network Theory. New York: Oxford University Press.

Manjapra K. Introduction. In: Colonialism in Global Perspective. Cambridge University Press; 2020:1-16.

McAfee, K. (1999). Selling Nature to save It? Biodiversity and Green Developmentalism. Environment and Planning. D, Society & Space, 17(2), 133–154. https://doi.org/10.1068/d170133

Mignolo, W.D. (2015) ‘On Pluriversality’. Convivialism Transnational. [Online convivialism.org/?p=199 accessed on 22 February 2021].

Novara Media. (2023). Richard Madeley LOSES IT At Guyana President Over Slavery. [Video] Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ike4EI_H-AQ

Parikka J. (2015) A Geology of Media. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Quijano, A. (2007) ‘Coloniality and modernity/rationality’, Cultural Studies 21 (2–3), pp. 168–178.

References

Robinson, C. J. (1983) Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition. London: Zed Press.

Salamanca, O. J. (2016) ‘Assembling the fabric of life: When settler colonialism becomes development’, Journal of Palestine Studies, 45 (4), pp. 64–80.

Vaughn, S. E. (2022). Erosion by Design: Rethinking Innovation, Sea Defense, and Credibility in Guyana. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 64(4), 849–877. doi:10.1017/S0010417522000329

Vaughn, S. E. (2024). Unavoidable Slips: Settler Colonialism and Terra Nullius in the Wake of Climate Adaptation. Critical Inquiry, 50(3), 494–516. https://doi.org/10.1086/728935

Velasco, A. (2020). Populism and Identity Politics. LSE Public Policy Review, 1(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.31389/lseppr.1

Weber, Max, 1864-1920. (1954). Max Weber on law in economy and society. Cambridge :Harvard University Press,

Wilson, S. (2008). Research Is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods. Nova Scotia: Fernwood Publishing.